Comments Reviews on theboatpeople.com Raft Cataraft Inflatable Kayak Products and Service › Forums › Environmental News › The Redwoods' Last Stand

Tagged: The Redwoods' Last Stand

- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 7 years, 12 months ago by

Lee Arbach TBP.

Lee Arbach TBP.

-

AuthorPosts

-

April 21, 2016 at 7:14 pm #2991

Lee Arbach TBPKeymaster

Lee Arbach TBPKeymasterThe Redwoods’ Last Stand

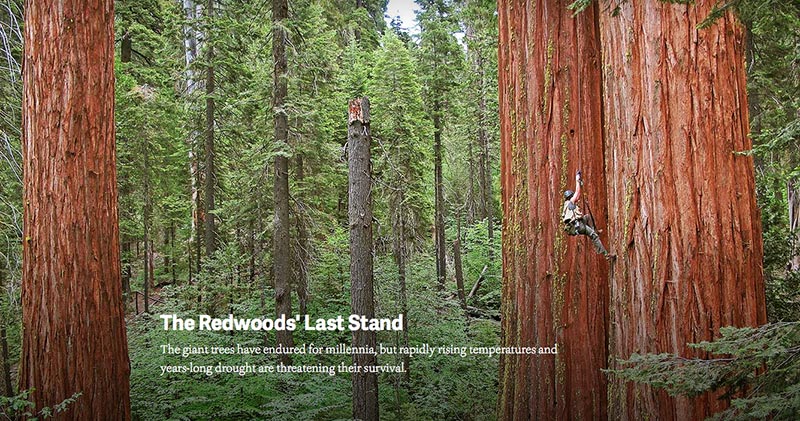

LOS GATOS, California—I’m dangling 180 feet off the ground in a harness, held by a single rope tied to a redwood tree named Joe. After a moment, I resume my ascent toward the canopy, a unique and largely unexplored ecosystem of mosses, lichen, and wildlife rarely glimpsed from the ground far below.On a neighboring skyscraper-tall redwood, Cameron Williams, a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, is rappelling to the pinnacle of an 850-year-old giant dubbed Grandfather. Williams, who has been climbing redwoods since 1999, has studied the impact of a record drought on the trees and has spent the past decade examining and documenting the hundreds of tiny plants that thrive in their upper reaches.

I started the hour-long ascent with my legs brushing some of the thousands of tiny cones and needles that stretch toward the sunlight. About 80 feet up, silence enveloped me as the ground below became obscured. The brain plays tricks—most likely out of self-preservation—morphing the thick foliage below into a safety net. As I hoist myself into the tree’s crown, there’s an overwhelming feeling of safety. The wind is blowing, but Joe the tree seems too large to sway.

FULL COVERAGE: Fight for the Forests

We’re not deep in some primeval forest but in a backyard near Los Gatos, an affluent Silicon Valley town nestled in the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains and best known as the home of Netflix. For one week a year, the landowner allows Williams and recreational-tree-climbing specialist Tim Kovar to lead four-person expeditions up Grandfather’s 12-foot-wide trunk and into the redwood canopy. It’s a rare opportunity—most surviving old-growth groves are under state and national park management and off-limits to climbing.

Grandfather’s trunk bears scars from where hundred-year-old branches had been chopped off. A previous owner had wanted to take the ax to the tree and the entire grove, only abandoning the plan in the face of community outrage. Today, after 160 years of logging, there remain just 120,000 acres of old-growth redwoods of the forests that once covered more than 2 million acres of California, from Big Sur to the Oregon border. Most now survive in state and national parks like the nearby Big Basin Redwoods State Park, which protects 11,000 acres of trees.

Coastal redwoods and their even bigger and longer-lived inland cousins, the giant sequoias, are not just trees that inspire awe in the most nature-averse city dweller. The largest organisms on Earth, redwoods and sequoias absorb more planet-warming carbon dioxide than any other trees. As scientists have recently discovered, the giant trees continue to grow and sequester carbon even after a thousand years. Their branches and house-size canopies shelter a host of endangered animals, from the northern spotted owl and marbled murrelet—a rare seabird—to the Pacific fisher and the Humboldt marten, two weasel-like critters.

Redwoods are built for survival. Their foot-plus-thick bark shields the trees from fatal fires, and a red-tinged chemical responsible for giving the trees their namesake color protects them against insects and fungus. They are the fastest-growing conifers in the world, reaching heights of 379 feet, with trunks 30 feet in diameter, leaving would-be competitors in the shade. Giant Sequoias grow on the western slopes of California’s Sierra Nevada and can live as long as 3,000 years. Coastal redwoods, which can live to be more than 2,000 years old, sprout along a 20-mile-wide, 470-mile-long ribbon on the continent’s edge, where ever-present fog supplies the trees with life-giving moisture and nutrients.Now that fog is fast fading away. Rising temperatures brought on by global warming are resulting in more fog-free days on the coast, while record drought deprives both redwoods and sequoias of water. The rapidity of the change in their environment wrought by the burning of fossil fuels threatens to overwhelm the giant trees.

“The climate changes that redwoods have seen in the past, they were taking place over millennia,” says Todd Dawson, a redwood expert and a professor at UC Berkeley. “It would take a thousand years for temperatures to change over two degrees. Now it’s taking three years.”

If the biggest, most formidable trees on the planet can’t survive climate change, can any?

Surviving Drought

Deep inside UC Berkeley’s Life Sciences building, Dawson stands amid molecule-separating mass spectrometer instruments—equipment he and fellow researchers use to study how redwoods are coping with climate change.

As the lab’s director, Dawson has studied redwoods for more than 25 years.

Redwood expert Todd Dawson in his laboratory at UC Berkeley. (Photo: Michael Short)

Early on, Dawson discovered the trees’ ability to extract water from the fog that often blankets the Northern California coast, absorbing moisture through foliage.

“There was literally nothing about the role fog played on coastal redwoods before we started looking in 1990,” Dawson says. In his office a few floors up from the basement of his lab, Dawson grabs a redwood tree slice leaning on his desk. He has it on hand to help illustrate the tree’s water-transporting characteristics to inquisitive students. His eyes light up behind his glasses as his hands travel over the hundreds of rings signifying hundreds of years of life.

“They not only take water up their roots out of the soil; they can take it up directly from their leaves at the top of the canopy, which means they don’t have to transport that water all of the way to the top of the canopy; it’s basically being taken out of the sky,” he says.

Now his team and other scientists are investigating how redwoods will cope with a lack of water and fog as temperatures rise and droughts become more intense and frequent. Fifteen of the 16 hottest years on record worldwide have occurred since 2001, and that sustained temperature increase has been linked to a drier and hotter California. That means lower snowpack levels in the Sierra Nevada, a vital water source for the giant sequoia during dry summer months.

A die-off of redwoods could have global implications. A 2012 study found that large trees older than 100 years store the bulk of a forest’s carbon, provide habitat for a third of wildlife species, and play a key role in the health of larger ecosystems. Disturbingly, the researchers discovered that big trees were dying at 10 times the rate of smaller trees around the world.

Dawson and his colleague Anthony Ambrose decided to get a closer look at how the drought was affecting redwoods. Ambrose has been climbing to the tops of these trees for more than two decades, and last summer he and fellow researchers spent more than 30 days installing humidity and temperature sensors on the upper limbs of 50 giant sequoia canopies.

UC Berkeley biologist Wendy Baxter takes data readings from equipment installed in a giant sequoia canopy. (Photo: Anthony R. Ambrose)

He selected four plots—two zones where ground surveys had shown trees were dealing with severe water stress and two zones where sequoias were faring better—in Sequoia National Park’s Giant Forest.

“The trees in the stressed areas were showing higher levels of dieback—where they drop branches and foliage—than we’d ever seen,” Ambrose says. “No one has documented or recorded dieback levels like we observed in the 125-year history of Sequoia National Park.” Some of the trees dropped nearly half their foliage between the summers of 2013 and 2014. An average summer sees sequoias drop around 5 percent of their foliage. With the dramatic leaf loss, the trees conserve water in their trunks and survive. It’s much easier for a tree to regrow branches, leaves, and cones than it is for it to try to regrow a stump.

“This method of shedding foliage is a really effective way the trees have of minimizing how much water stress they experience,” Ambrose says. “It’s basically like a safety valve to make sure the main trunk doesn’t die.”

In comparing the plots, the researchers found that trees with record dieback were no more water-stressed than trees showing lower foliage loss.

“These trees are remarkably resilient to drought; they’ve survived thousands of years going through extreme weather events, and overall, we’re not seeing the mortality events in sequoias we’re seeing in other tree species,” Ambrose says.

So have the sequoias averted disaster, especially as El Niño soaks the Sierra after four years of record drought? At his Berkeley lab, Dawson isn’t so sure.

“With this most recent drought, I think we’ve hit a tipping point,” he says. “The trees may have been able to cope with the water stress, but the canopy loss recorded in these 2,000- and 3,000-year-old trees—we’ve never seen a four-year period like this.”

Now Dawson fears the remaining 75 giant sequoia groves scattered across the mountainous 250-mile Sierra Nevada range won’t have enough time to recover. The higher temperatures and drought that have sapped California for the past four years could be the new normal.

“All of the records we have go back millions of years, from ocean sedimentary cores, and all of the really long-term records allow us to measure how climate has changed on the earth over time, but we have never recorded any changes with the velocity that we’re seeing today,” Dawson says.

Fire Season

Climate change is complicating environmental scientist Portia Halbert’s efforts to preserve ancient redwood groves at Big Basin. Some 90 years of wildfire suppression has put the 2,000-year-old trees at grave risk.

An eight-foot-wide slice of one redwood is mounted outside the park’s headquarters, its yearly growth rings marking the march of time. The first ring dates from 544 A.D., the year of the tree’s birth. The redwood was 948 years old when Columbus landed on America’s shores. In 1936, the year it turned 1,392, the tree died at the hands of loggers.

For most of the tree’s life, fires naturally raged through the redwood forest every decade or so. Then a Smokey Bear ethos took hold.

“For years, we operated under the idea that forest fires were all bad, so we fought to stop all of them,” says Halbert, decked out head to toe in the wildlife ranger green of a California Department of Parks and Recreation uniform as she walks along Dool ridge just north of Big Basin’s famed redwood loop trail—home to the 293-foot-tall Mother of the Forest tree. The ridge separates designated burn plots in the park.

But redwoods aren’t just fire-resistant; they’re also fire encouragers, Halbert says while crouching down and digging into the mulch at the base of a tree… please go to link to finish report

http://www.takepart.com/feature/2016/04/18/racing-save-ancient-redwood-forests-climate-change?cmpid=tpdaily-eml-2016-04-21 -

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)